Let's all be Jean Valjean, guys

What do Elon Musk and Victor Hugo have in common? The potential of Luke 19.

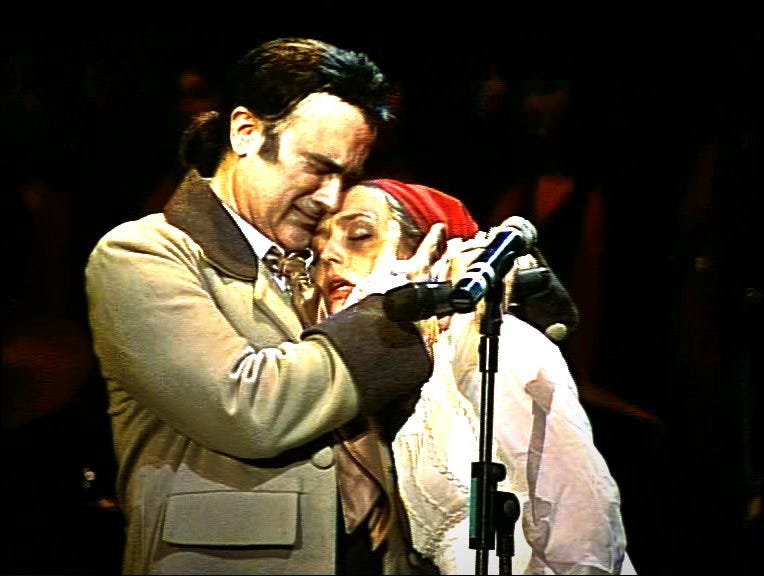

During my senior year of high school, I played the character of Eponine in a performance of Les Miserables. From stage, I belted the beautiful but kind of creepy song, “On My Own” while clad in a shabby black dress, a red sash draped across my chest representing Eponine’s involvement in the French Revolution. I loved the character and at the time, identified with her complex personality—her fiery sense of justice and her angsty, lonely teenage persona.

I didn’t fully grasp the story of Les Miserables until I saw it performed in London at the Queen’s Theater in 2007. I’d arrived to the show to find upgraded seats, third row center and could practically reach out and touch the actors, they were so close. Watching it as a fully grown woman who’d already lived through some tragedy, heartbreak, and brokenness in my 9 years of adulthood at that point, I immediately recognized the theme of mercy woven so tenderly through the drama. I was reminded that God’s own heart for mercy is just as strong as his desire for justice and it was difficult to remain composed. Tears came. It was a whole thing.

Right now, I’m reading the novel by Victor Hugo, where the play was originally drawn from, and experiencing the same range of emotions all over again. But because of the way novels were constructed during this time—they were originally published as fragments in magazines—the book is a long one, almost 1,000 pages, and contains more storylines and characters that add texture to the already thematically heavy novel.

If you’ve seen the play or film, you know who Marius is: the brave, young romantic who falls in love with the beautiful Cosette. But the book goes much deeper into Marius’ family background than the stage production does. Hugo expertly compares Cosette’s adopted father, Jean Valjean—a former criminal-turned-saint—to that of Marius’s own grandfather who raised him: Father Gillenormand. While Gillenormand’s version of “love” is conditional, selfish, and co-dependent—more about what he can receive from his relationship with Marius than what he’s willing to give—Jean Valjean is self-sacrificial toward Cosette, honoring her freedom and wishes even though it causes him pain. It wasn’t about him; it was about making sure Cosette had a better life than he had.

Reading this showed me yet another way God has revealed Himself in literature or art without the artist really understanding what’s happening (or maybe he did, who knows?).

When most people (even Christians) think of religion, they immediately think of all the rules they have to follow in order to practice that particular faith. It’s often about, “so what do I have to give up in order to do this?”

Sure, we have to lay our entire lives down—like everything—but why would you want to do that unless you knew the real reason you’re doing it? What good could possibly be on the other side of it? Heck, I would not want to have anything to do with Christianity unless I really knew it was gonna be worth it. Unless I knew Jesus was really, truly worth losing my life for.

Apart from Jean Valjean being a totally imperfect, flawed human being (who eventually encounters redemption), I recognize him as a kind of Christ figure in this novel. He came to undo the effects of the sin of Cosette’s mother by rescuing Cosette and redeeming her life. He forgives Inspector Javert multiple times after he repeatedly tries to destroy Valjean. And though he deeply loves Cosette as a father would, he lays down his life for her, risking his own loss, so she can make choices leading her to become the woman he has taught her to be.

That’s a good father right there. And God, the Father, is markedly better than Jean Valjean ever was.

Father God let me make a lot of bad choices over the years. Choices that I kept making over and over, like a dog returning to its vomit (Proverbs 26:11). He didn’t try to control me, He just let the consequences happen because that’s how we grow. That’s the brutal reality for many of us who don’t learn the hard way even after a few hundred times. I learned that laying my life down meant actually experiencing the supernatural love of God and gaining a new life in the fullest way possible. Not with money, not with material success but with knowing Christ Jesus, my Savior (Philippians 3:8-10). What I had been living in was death warmed over—every single day. But letting God love me in my mess was something … extraordinary.

In Luke 19, in the Bible, Jesus meets a rich tax collector named Zacchaeus. Zac was Jewish but was hated by his own people who saw his position, working with the Roman government, as a betrayal. He was greedy and unkind and didn’t have many friends.

For a moment, imagine who your own Zacchaeus would be. Is it your mother-in-law? Co-worker? Boss? Kamala Harris? Joe Biden? Elon Musk? A transgender or gay rights activist? Mine, right now, would be Donald Trump. Or better yet, any Christian who voted for him, campaigned for him, or supports him. Donald Trump is my Roman government.

I’ll use someone who doesn’t profess Jesus as an example because Christians do need to hold each other accountable. This is about how we view people don’t know Jesus.

I’m imagining I’m a disciple hanging out with Jesus—the Son of God—and as I’m walking along with Him, He sees Elon Musk in the street and is like, “Hey Elon. I’m coming over to your place for dinner tonight. Let’s get going.”

I’d obviously be like, “Jesus, what are you thinking? That guy is reprehensible. He’s an immoral, racist, right-wing wacko. Why would you EVER hang out with him?”

And Elon is like, “Really? Me? You’re coming to my house?” And because I’m a disciple, I have to come too. And ya’ll, I’m so embarrassed to be seen with this guy. What will my friends say when they see me eating with Elon Musk of all people?

Gross.

So we eat with Jesus and Elon Musk, and I’m right: everyone is mocking us. I notice that Jesus isn’t pointing out Elon’s sin. He’s just talking to him like a friend, like He does with Zacchaeus in Luke 19. He’s not yelling at Elon or bullying him into confessing his sin. He doesn’t say a thing to Zacchaeus about his nasty, racist remarks, his obsession with authoritarianism, his fathering of 8 children with multiple women, or his greed. He just loves on Elon and lets the Holy Spirit work on his heart.

In the end, just like Zac, Elon is feeling pretty loved and confident in Jesus’ affection for him. He’s confident that Jesus is for him and for his good. It doesn’t take Jesus giving him a guilt trip for Elon to repent. He is attracted to Jesus and wants more of His friendship and he knows that to be really close to Him, he has to stop acting like a fool.

“Look, Lord! Here and now I give half of my possessions to the poor, and if I have cheated anybody out of anything, I will pay back four times the amount (Luke 19:8). And I repent of my politically power-hungry, bullying ways. I will stop using women to feed my ego, irresponsibly producing more children than I could possibly father. I will stop promoting racist and anti-immigrant ideologies. I just want to be near you and follow you! (emphasis added by myself).”

Wow, you guys. That was convicting. You should really try it yourself.

“Or do you presume on the riches of his kindness and forbearance and patience, not knowing that God's kindness is meant to lead you to repentance?” (Romans 2:4)

Like Gillenormand, it's our sin nature to love people because they benefit us and to hate people we fear. We try to control the sin of others by bullying and by using our political power but in the end, that shows our lack of love. Gillenormand controlled Marius, preventing him from knowing his father, a good man, because he wanted Marius all to himself. Jean Valjean knew that love looked like letting Cosette have the freedom to find love for herself.

He let her heart be wooed by her suitor and she was safe to let it be pursued, because she had learned what love looked like through Jean Valjean.

Let’s all be Jean Valjean, guys.